The cultural power of Pink Floyd is almost entirely bound up with the early Seventies, a time of burgeoning progressive rock in the aftermath of the hippie era, of extravagant stadium tours, general lifestyle excesses and a time when the rock star myth still had cachet. So it’s initially quite strange to think of them as a presence at the dawn of the internet age in 1994, in the context of a music scene dominated by the post-Nirvana explosion in alternative rock on one side of the Atlantic, and the arch, knowing irony of Britpop on the other. But it was the year that saw the release of The Division Bell, the 14th and final Pink Floyd album, and one that fans of different generations hold in equally high regard even in 2019.

Despite the group’s bassist, singer and songwriter Roger Waters isn’t present, having quit Pink Floyd around a decade earlier following a power struggle in the wake of 1983’s middling The Final Cut, the album is one of the most distinctive and characterful albums the band ever made. However, considering the lofty reputation it holds, there was barely anything that was surprising or strikingly original about The Division Bell. David Gilmour’s guitar echoes with ghostly reverb, but more clearly and warmly than before; his lyrics were introspective and fraught with worry, yet cautiously hopeful; Nick Mason’s drums and session musician Guy Pratt’s bass provide a stately and sturdy chassis for the songs, and Richard Wright’s keyboard textures act as sublime decorative features.

The warm reception it garnered, racing straight to the top of the charts on both sides of the Atlantic as well as 11 other countries in the late spring, seemed to be based on the sense that Pink Floyd, at long last, had rediscovered their classic form. Like a footballer enjoying a vintage season in their mid-thirties after a few rocky years of speculation about terminal decline, Pink Floyd’s fans were able once again, after 15 years of silence punctuated by a mere two albums (and mediocre ones at that), to say that their favourites still had it.

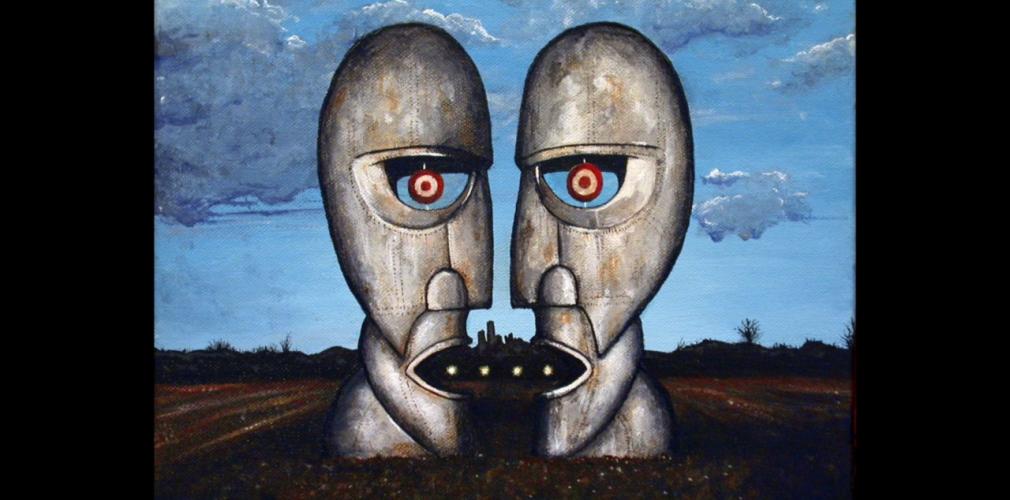

Conceptually, The Division Bell was much more thematically and musically unified and uniform than A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, the group’s previous album released nearly seven years before. It was a theme cleverly reflected in the album’s artwork made by legendary designer Storm Thorgerson and his Hipgnosis agency. The two massive statues, both three metres in height and made from metal, were actually photographed in a field near Ely. The image can be seen as two halves of a singular face, or as the faces of two people talking to each other, evoking a theme of unity and peace achieved through talking to each other, and this was something immediately detectable in The Division Bell’s music, where communication and diplomacy were recurring topics.

The sparse, restful qualities of the instrumental opener ‘Cluster One’ allow The Division Bell to unfurl in an almost cinematic manner. Producer Bob Ezrin, who helmed The Wall and was once again working with Pink Floyd in its new Gilmour-led incarnation, had by now become in expert in capturing that sense of suspended, heightened reality that the group’s very best work instills in the listener.

The early-to-middle sections of the record seems to pass by in a pleasant fugue, connected with abstract whirls of keyboards and sharing all sharing slow, ruminative rhythms. The beautiful ‘Poles Apart’, featuring an almost folky guitar motif and underpinned by a sparky but dream-like rhythm, is a reflective exploration of Pink Floyd’s past. Gilmour wouldn’t be drawn on its meaning initially, despite being more open on the overall meaning of The Division Bell than previous albums, but his wife Polly Samson, who co-wrote many of the album’s lyrics, later confirmed that its first verse was about Syd Barrett, and the second about Roger Waters. Inspired by a domestic row with Samson which was down to lack of communication, ‘What Do Want From Me’ strongly features Gilmour’s guitar driving a lumbering behemoth of a rhythm.

A similar musical and thematic motif re-appears on the album’s thematic centerpiece ‘Keep Talking’, a plea for reason and diplomacy built around a sample of Professor Stephen Hawking’s electronic voice from a BT ad. It’s curious to think that such a moving piece could be inspired around something as prosaic as an advertisement, but David Gilmour was said to be so awestruck by its sentiment that he broke down in tears and immediately sought clearance to sample it.

Appearing as the ninth track, ‘Keep Talking’ kicks off a breathtaking trio of songs that both encapsulate the themes of The Division Bell and end it on a real high note. ‘Lost For Words’, explicitly dealing with rivalry and forgiveness and co-written with Samson, has a downbeat yet anthemic quality, and the tolling bells that bookmark the atmospheric closer ‘High Hopes’ send shivers down the spine, as Gilmour touches on the fragile nature of societal progress, and how easily it can get undone (“Steps taken forwards but sleepwalking back again / Dragged by the force of some in a tide”).

But arguably the most moving moment for the band’s long-term fans was ‘Wearing The Inside Out’, the first Pink Floyd track to feature a lead vocal from the long-suffering Richard Wright since The Dark Side Of The Moon over two decades before. It had taken British experimental composer Anthony Moore to help Wright get his words down on paper, and his vocal performance itself was heartbreakingly raw and down-trodden, with harrowing lyrics like “Extinguished by light I turn on the night / Wear its darkness with an empty smile” speaking of deep sadness and disappointment.

25 years on from its release, The Division Bell increasingly seems like a fitting epitaph for the Pink Floyd story, full of grace, confidence and dignity, even though it was made without one of its most important figures. Indeed, it was The Wall a full decade and a half earlier that featured all four of what most people generally regard as the Floyd’s classic line-up. That didn’t seem to bother their fans though: on the back of a six-month, box-office busting world tour, which ended with a 14-date residency at London’s Earls Court and which spawned a breathtaking live album Pulse the following year, The Division Bell resonated keenly with Pink Floyd fans.

Just over twenty years later in late 2014, a record of instrumental out-takes and ambient snippets from The Division Bell’s sessions was pieced together and mixed by David Gilmour and Youth to make The Endless River. While it makes little sense outside of the context of its parent album, it served as a neat epilogue to Pink Floyd’s career, alongside setting the record for Amazon’s most pre-ordered album of all time.